14th Engineer Regiment, Philippine Scouts

Organized

May 2, 1921 from elements of the First Philippine Engineers (Provisional) (PS) and the 62nd Infantry Regiment (PS)

Redesignated

1946 as the 56th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS)

Disbanded

July 15, 1953 as the 514th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS) [1]

Regimental Day

May 2

Campaigns

Philippine Islands 1941-1942

Citations

Distinguished Unit Citation

Philippine Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation [3]

The 14th Engineer Regiment (PS) assembling a pontoon bridge during a river-crossing maneuver, 1940.

The 14th Engineer Regiment, Philippine Scouts, was an element of the Philippine Division, U.S. Army, based at Ft. McKinley. Organized in 1921, this organization can trace its lineage all the way back to 1900 with the formation of the Leyte Scouts (later the 37th Company (PS)).

As the primary Army engineer unit, it played the ever-critical role of mapping the Philippine Islands, building roads, and fortifying the islands, especially the Bataan Peninsula prior to WWII. In writing about the 14th Engineers (PS), Colonel John Olson of the 57th Infantry (PS) said:

“There was probably no other unit in the American Army in the Philippines… that did more to strengthen the defenses than the 14th Engineer Bn (PS).” [2]

For the regiment’s actions during WWII, the 14th Engineers (PS) earned a Distinguished Unit Citation and one Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. The Army awarded a number of decorations to the officers and enlistedmen: 2 Silver Stars, 5 Bronze Stars (2 with Oak Leaf Clusters), and 103 Purple Hearts (4 with Oak Leaf Clusters). After blazing trails all across Bataan and spending the last few days of the campaign as infantrymen, the 14th Engineers (PS) surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942.

The Army redesignated the unit as the 56th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS) in 1946. At some point, it was redesignated again as the 514th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS) and disbanded in 1953.

History

Pre-organization

Originally organized on September 1, 1900 as the 2nd Company, Leyte Scouts on the Barago Island of Leyte [4]

Redesignated as B Company, Leyte Scouts (Quartermaster), mustered out June 30, 1901

Re-mustered on July 1, 1901 as the 37th Company, Philippine Scouts

Engaged in fighting insurgents and the Pulajanes. Conducted quarantine duty during the Rinderpest epidemics. Also tasked with topographical work, erecting permanent and semi-permanent posts, and temporary camps constructed of bamboo and nipa.

Army organizes the 1st Philippine Engineers (Provisional) Battalion on April 7, 1918 at Camp Nichols, Rizal, P.I.

37th, 85th, and 86th Companies of the PS designated A, B, and C Companies of the First Philippine Engineers (PS)

The 37th Company (PS) was split three ways, reallocating soldiers to each of the three companies of the First Philippine Engineers (PS): 27 to Company A, 25 to Company B, and 25 to Company C

Formation

The Army organized 14th Engineer Regiment (PS) on May 2, 1921 [5]

The First Philippine Engineers (PS) Headquarters and Service, A, B, and C Companies were redesignated as H&S, A, B, and C Companies of the 14th Engineers (PS)

Men from the inactivated 43rd Infantry (PS) were reassigned to the 14th Engineers (PS) to fill in the ranks

Companies E, F, and I of the 62nd Infantry (PS) were redesignated as Companies D, E, and F of the 14th Engineers (PS) on September 16, 1921

Interwar

After World War I, the US Army started to reduce in size. On September 12, 1922, the Army placed the 14th Engineer Regiment (PS) on the inactive list, except for the 322 men and officers of the First Battalion and one battalion section of the H&S Company. The rest of the men were reassigned to the Coast Artillery companies on Corregidor. [2]

During the interwar period, the Army tasked the 14th Engineers (PS) with mapping the islands, erecting posts and camps as well as road and bridge construction and maintenance, and demolition. They also trained to lay mines, booby traps, wire and road obstacles. After 1935, the unit even provided instructors to the Philippine Army Engineer School and later the Philippine Army engineer units.

Panorama of the 14th Engineer Regiment (PS), October 9, 1937. (Courtesy of Read Hanmer)

Throughout the 1930s, the 14th had been preparing the Bataan Peninsula, cutting trails, upgrading roads to all-weather status as well as constructing bridges. One of the huge accomplishments of the officers and men was creating a fully detailed map of all the new roads and trails on Bataan. They also dammed the Pilar River to create a possible obstacle if the enemy were to invade the lower half of the peninsula.

With Major General Grunert taking command of the Philippine Department in 1940, he began preparing the Philippines for war. Not only did he work to update War Plan Orange, No. 2 (WPO-2), he also ordered the 14th Engineers (PS) to build a reserve depot on Bataan on the bluff above Mariveles. Here, the engineers constructed bodegas for storing ammunition and other supplies. Little did they know they were constructing, “Little Baguio,” the US Army Forces in the Far East’s headquarters during WWII. [6]

The 14th Engineers (PS) building a bridge on the Bataan Peninsula, 1937, (Courtesy of Read Hanmer)

Corporal (later Captain Mar Arradaza) commented, “As an example of the extra efforts of the 14th Engineers (PS)… 1st Sgt. Saturnino Padua required the recruits to practice with the 1903 Springfield bolt action rifle on the floor of the barracks in the evenings, so his company had 100% qualification with 71% experts and 29% sharpshooter—a real show of dedication.”

Leading up to the war, the 14th had many officers and non-commissioned officers on detached service to train the engineers of the newly formed Philippine Commonwealth Army. In early 1941, the Army authorized the expansion the unit to 544 men, and further expanded it in November 1941 to 938. The ranks were filled in by men working for gold mining companies in the Mountain Provinces. Even the regimental commander, Harry Skerry, was reassigned to the North Luzon Force Headquarters on December 4, 1941. Although an aviation engineer battalion, the 803rd, provided some assistance starting in November 1941 and the Philippine Army engineers conducted smaller-scale tasks, it was up to the 14th Engineers (PS) to keep preparing the defenses for war.

World War II

On December 8, the Imperial Japanese Forces began an air assault on the Philippines. The 14th Engineers (PS) took paratroop defense positions: HQ and HQ Company stationed near the Pan American Airways building at Nielsen Airfield. Company A was east of the airfield, Company B was north. Platoons of Company C were at the junction of Pasay Road and Circumferential Road, digging foxholes around Division HQ, or at Burgos working on an Air Warning site.

At 0315 hours on December 9, the Japanese conducted a heavy air raid near the Pan American Airways building at Nielsen Airfield. Three men of the 14th Engineers (PS) that were on duty were struck by bomb fragments nearby. Private De La Cruz died the following day from his wounds. They would be the first WWII casualties of the Philippine Division.

On the 10th, the 14th formed combat teams and the companies moved out to join their respective infantry regiments: Company A to the 57th Infantry (PS), Company B to the 45th Infantry (PS), Company C to the 31st Infantry. Headquarters moved to Orani, Bataan to take up their positions. While with the 31st Infantry, Company C destroyed the chromatic mines and the pier at Masinloc, Zambales to prevent the enemy from using it. During the retreat, Company C was the first into combat when they became targets of Japanese artillery while attached to the 31st Infantry.

In early January 1942, the Bataan Defense Force was formed and the combat teams were dissolved, so all companies reverted back to the 14th Engineers’ (PS) control. Companies A and B started to cut new roads, laid more than 2,000 along the whole 57th Infantry’s (PS) front, set up barbed wire, and also set up water points, and a 50 dummy artillery pieces that drew enemy artillery fire. After doing so, Company A blew up a bridge on the East Road and supervised the infantrymen setting up barbed wire. Company B worked to improve the road from Bani to the front. And Company C did road improvement around the Bani area. [7]

The Japanese outflanked the II Philippine Corps line on the eastern side of the peninsula. Platoons of the 14th were attached to the 45th and 57th Infantries (PS). They were dispatched to stop the Japanese from landing on the western side of the peninsula during the Battle of the Points and successfully did so.

USAFFE Headquarters placed the battalion in Army reserve on January 30 and deployed to do various engineering tasks, such as road construction and carving trails. Then on February 5, USAFFE gave the 14th (minus the platoons attached to the 45th and 57th Infantries (PS)) a major task. As 2nd Lt. Kramer of C Company recounted the mission:

“…to build a new [east-to-west] 10 mile road across Bataan behind the Bagac-Pilar Road, some of which was too close to enemy lines and fire. It was a prodigious task to cut through the jungle slopes on northern Mt. Mariveles. Often, the visibility was only 10-100 yards, over the Pantigan River gorge with some 2,000 feet down to the valley floor. When completed—one day ahead of schedule—the road would allow lateral movement of reserves as well as supplies, as it ran just behind the regimental reserve lines.” [7]

During the lull from mid-February to March 12, they constructed beach defenses from along the Bataan coast from Limay to Bagac. On March 12, the 14th was placed under Luzon Force Headquarters, moved to Signal Hill KP186, and held in reserve to be used as combat infantry at a moment’s notice.

On April 3, the 14th was alerted to move to “Little Baguio,” the reserve depot they constructed back in 1940. “On the night of 5 April the battalion left all tools behind and moved to the junction of Trails 2 and 10 to be ready for combat the next morning.” To the west of them, the 57th Infantry (PS) command post. In front, the 26th Cavalry (PS). Kramer continued:

“All that night and the next day we shot and we were shot at, never seeing the enemy face to face due to the thick jungle we were deployed in—we heard that “B” Company—was in some heavy fighting on our right.” [8]

The 57th Infantry (PS) and remnants of the 21st, 31st, and 41st Philippine Divisions were alternatively firing and falling back toward the 14th. Soldiers of these units staggered through the engineers’ line in the afternoon of April 7th. Corporal Arradaza described the day:

“As the day was turning to noon, more bad news was coming in from the front. Mortar and small artillery shells from the enemy had been falling into our position since 1000 hours. Our "[B] Company Commander ordered our trucks to line up on Trail 2, facing west and uphill and all our crew served weapons and all ammunition loaded in the trucks… We were almost ready to load into the trucks when 6 planes came back and unloaded their bombs and strafed us. We were really caught as all of their bombs found their targets, killing 3 men in our squad and wounding another two. All the vehicles were hit and the ammunition exploded in every direction. [8]

“…We kept moving. We were very tired and very thirsty. We just had walked about a mile when we were ordered to halt for a rest of about 30 to 45 minutes. We kept moving all night and finally heard shouts of joy. Happy men were in the Alangan River quenching their thirst. I dipped my mouth even at the edge and drank as much water as I could. It seemed that my body relaxed and my tiredness was gone from drinking almost a gallon of water.

“While crossing the stream, we had overtaken two bull dozers towing 105 howitzers. I heard someone say that they were going to bury them. I never had the slightest idea that our effort of defense was coming to an end…” [9]

Throughout the day on April 8, they continued to move and dug a defensive position to the left of Trail 20. C Company held the left flank and to the right were three troops of the 26th Cavalry (PS). B Company, 14th Engineers (PS) was in reserve. The enemy appeared with tanks and infantry. The engineers engaged them and forced them to deploy. The enemy tanks were held up by the dense forest as well as rock obstacles that the Scouts had placed on the trail. The Scouts held the enemy off. A withdrawal order was given and A and C Companies moved past B Company to the rear. The Japanese did not pursue.

The 14th continued to move through the night until it reached the Cabcaben area where they found a truck loaded with rice. As they tried carrying it, Corporal Arradaza met some civilians who said “it’s no use as they heard on the radio that the [Japanese] had captured some high ranking Army officers.” The corporal ran to join the rest of the battalion where the battalion officers while they held a conference. “One of our platoon overheard the conversation which was that after breakfast, they were going to turn us loose and we would be on our own.”

Once the surrender was confirmed, the Scout officers advised the Scouts to shed their military clothes and get through the enemy lines as civilians. The officers could not disguise themselves, so a group of them walked to the bivouac at Signal Hill, awaiting the enemy. Several officers, like Lt. Kramer, escaped the. peninsula. The 14th Engineers (PS) ceased to be a unit by the afternoon of April 9.

The 14th Engineers (PS) had 309 fatalities, with 31 deaths from war actions, 238 in the Death March, prisoner of war camps, and ships. 40 were from unknown causes.

Collectively, the officers and enlistedmen of the 14th Engineers (PS) earned 2 Silver Stars, 5 Bronze Stars (2 with Oak Leaf Clusters), and 103 Purple Hearts (4 with Oak Leaf Clusters. For certain there were other awards that should have been given out, but the final paperwork was not processed before the surrender. Additionally, the 14th was awarded the Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation for services rendered from 8 December, 1941 to 9 April, 1942. [9]

During WWII, a number of 14th Engineers (PS) escaped and fought with the guerrilla forces. Once the US forces returned to the Philippines and liberated the country, the Philippine Scouts returned to US military control. They were assigned to one of eight military police battalions until the end of the war.

Post-WWII

In 1946, the US Army reorganized the Philippine Scouts into “New” Philippine Scout units. One such organization was the 56th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS) and eventually redesignated the 514th Engineer Construction Battalion (PS) until disbanded in 1953.

After disbanding the Philippine Scout units, many Philippine Scouts reenlisted in the US Army, some serving for decades. One such soldier, Technical Sergeant Melchor V. Diokno of B Company, 14th Engineers (PS), fought on Bataan, survived the Death March, fought with the guerrillas, and reenlisted after the war. He was eventually commissioned as an officer in the US Army, rising to the rank of Major, retiring in 1957. His story exemplifies one of the many Scouts that continued to serve even after the disbandment of the 14th Engineers (PS) and the rest of the Philippine Scouts.

The group photo is from 1945, showing some of the survivors of C Company, 14th Engineers. My Dad, then a Colonel, is in the middle. He was delighted to establish contact with his former soldiers, and was able to help many of them after the war. He returned to the States in 1947. (Courtesy of Read Hamner)

Regimental Commanders [1]

Regiment

Lt. Col. Francis A. Pope

May 2, 1921 - July 2, 1923

1st Battalion

Maj. Houston G. Parrott

May 23, 1921 - December 31, 1922

Capt. Frank Tillotson

December 31, 1922 - July 2, 1923

Capt. Thomas F. Wirth

July 2, 1923 - September 17, 1923

Capt. Horatio G. Fairbanks

September 17, 1923 - October 17, 1923

Maj. Charles E. Perry

October 17, 1923 - July 16, 1924

Regiment

Maj. Charles E. Perry

July 16, 1924 - December 11, 1925

Maj. Elihu H. Ropes

December 15, 1925 - December 1, 1927

Capt. Daniel L. Hooper

December 1, 1927 - February 10, 1928

Maj. Robert A. Sharrer

February 10, 1928 - March 3, 1930

Maj. Albert K. B. Lyman

March 4, 1930 - January 16, 1932

Capt. Roy M. McCutcheon

January 16, 1932 - February 27, 1932

Maj. William H. Holcombe

February 27, 1932 - June 28, 1935

Lt. Col. William M. Hoge

June 28, 1935 - October 29, 1937

Lt. Col. Edwin C. Kelton

October 29, 1937 - July 19, 1939

Lt. Col. Henry W. Stickney

July 19, 1939 - July 20, 1940

Lt. Col. Harry A. Skerry

July 20, 1940 - December 4, 1941

Lt. Col. Frederick Saint

December 4, 1941 - April 1942

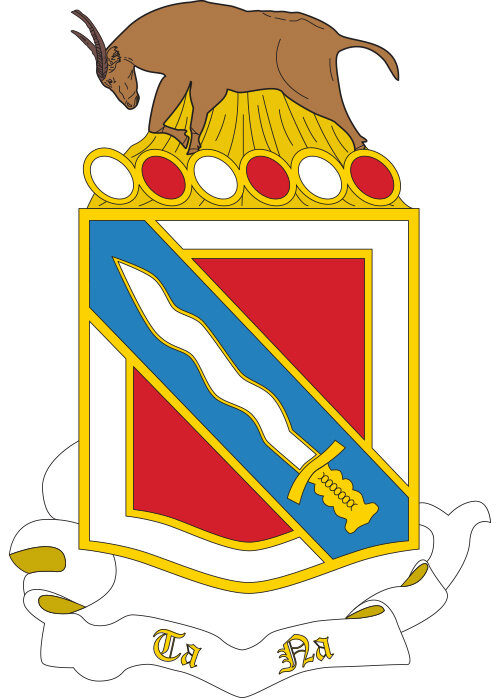

Insignia and Coat of Arms

Distinctive Unit Insignia

Shield: Gules, a narrow bordure argent, on a bend azure fimbriatel or a kris of the second hilted of the fourth.

Crest: On a wreath of the colors, argent and azure, a charging carabao proper.

Motto: “Ta Na”

Approved: December 23, 1921

Meaning: The shield is of red and white, the color of the Engineers. The blue “scarf-like” bend of infantry blue and gold adorned with a kris, a trophy captured by its predecessor, the 37th Infantry Company, Philippine Scouts. The crest consists of a charging carabao, a patient and peaceful beast of burden, but fierce, brave, and courageous when aroused. The motto is in the Visayan dialect and means “Let’s go.”

Coat of Arms

One was not approved for this unit.

Distinctive Insignia of the 14th Engineer Regiment (PS). (Courtesy of the “Ta Na” Collection)

The redrawn regimental colors of the 14th Engineer Regiment (PS) (Courtesy of Sean Conejos)

Bibliography

[1] “14th Engineer Regiment (PS).” US Army Order of Battle, 1919-1941, by Steven E. Clay, vol. 3, Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010, pp. 1702–1703.

[2] “14th Engineer Bn (PS).” The Philippine Scouts, by John Olson, Philippine Scouts Heritage Society, 1996, p. 222.

[3] “Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register.” Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register, The Army, 1961, p. 55.

[4] Olson, 221.

[5] Olson, 220.

[6] Olson, 223.

[7] Olson, 232.

[8] Olson, 233.

[9] Olson, 236.